Cities evolve constantly, and this week I’ve been reflecting on the visionaries and forces, both past and present, that continue to shape the world around us.

In this week's edition:

Frank Gehry: A Singular Voice

The Lever House Story

Brooklyn’s Townhouse Boom

Public Markets: The Changing Landscape

Frank Gehry: A Singular Voice

“Architecture should speak of its time and place, but yearn for timelessness.” — Frank Gehry

Frank Gehry, who died this week at 96, was widely regarded as one of the most influential architects of the last century. As The New York Times noted, Gehry redefined what architecture could be: emotionally expressive, culturally catalytic, and unbound by the linear logic that dominated so much of modern design. The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao became a global turning point, transforming an industrial city into a cultural landmark and proving that architecture could reshape both civic identity and economic destiny.

Throughout his career, he continued to evolve, producing buildings of enormous complexity and surprising delicacy, from the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles to the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris.

As Architectural Digest reflected, Gehry never saw architecture as static. He treated surfaces like brushstrokes, metal like fabric, and public space as something alive. His structures bent light, played with movement, and embraced irregularity with intentionality. AD highlighted how Gehry’s designs often balanced the monumental with the intimate: museums that invited wandering, concert halls tuned for warmth, and sculptural forms that were simultaneously futuristic and deeply human. His signature materials — titanium, glass, laminated wood — became tools for expressing emotion as much as structure.

Late in his life, Gehry remained astonishingly prolific. The NYT observed that even in his nineties he was sketching late into the night, taking on major cultural commissions, and mentoring younger architects who saw in him not just a master of form but a believer in curiosity, risk, and reinvention. Together, these tributes capture a portrait of an architect who altered skylines, disciplines, and imaginations, and whose influence will reverberate for generations.

For me, Gehry’s work has always been a reminder that great architecture can move us — it can evoke wonder, shift perspective, and stay with us long after we walk away. His passing leaves a void, but his vision endures.

A rare and singular voice, and one we will feel the absence of for a long time.

Left: The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, completed in 1997.

Right: The 76-story residential tower Mr. Gehry designed in Lower Manhattan, completed in 2011.

Mr. Gehry’s sculptural New World Center concert hall opened in Miami in 2011.

The Story of the Lever House

Gehry’s work expanded the emotional vocabulary of architecture. Here in New York, we have our own icons that did the same in their time, including one landmark that quietly changed an entire era of design.

If you walk down Park Avenue, your eye naturally goes to the giants. Glass towers, corporate headquarters, the familiar skyline silhouettes. But tucked quietly among them is a teal building that seems almost modest in comparison. It does not fill its entire lot. It is easy to overlook. Yet this unassuming structure, Lever House, reshaped the future of New York’s skyline.

After World War II, architecture shifted toward a clean, boxy international style.

Lever House wasn't the first building of this movement in New York, but it became the one that defined how modern corporate towers would look and function. Its genius had to do with zoning and timing.

New York had operated under the 1916 zoning resolution, which required tall buildings to taper back from the street. That rule gave us many of the city’s beloved wedding-cake skyscrapers. But a long stretch without new construction during the Depression and the war meant that by the 1950s, design tastes and building technology had changed dramatically.

When Lever Brothers set out to build their headquarters in 1952, they wanted something light, transparent, and forward-looking. The setback rule stood in the way. So the architects, Gordon Bunshaft and Natalie de Blois of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, found a loophole. If they built on only a quarter of the lot, they could avoid the setbacks entirely.

And so they made a decision that no developer in the city had ever made before. Instead of maximizing the land, they left most of it open. A slim 21-story tower rose from a 2-story base that functioned as a public plaza. The gesture was radical for its time. It set a new precedent for how corporate architecture could look, and more importantly, how it could meet the street.

Lever House also broke technical ground. It was the city’s first fully glass curtain wall skyscraper and the first office building sealed with non-operable windows and full air conditioning. A new idea of what an office tower could be emerged right there on Park Avenue.

The building became so influential that it helped shape the next major zoning overhaul in 1961, which encouraged developers to create public spaces in exchange for more height. Whenever you see a small garden or plaza at the base of a very tall building, it is often drawing on the path Lever House paved.

It is remarkable to think that one compact teal building, hiding in plain sight among giants, ended up rewriting the rules of the skyline.

The Brooklyn Townhouse Builder Boom

From Midtown’s modernist breakthrough to Brooklyn’s low-rise reinvention, the city keeps rewriting the rules of scale, material, design. Here's a trend unfolding in townhouse development

There's a quiet shift taking place in Brooklyn’s luxury market. Over the past few years, a new kind of developer has emerged across Brownstone Brooklyn. These are the townhouse specialists who look at a modest multifamily building or a narrow vacant lot and see possibility. The result has been a steady rise in single family restorations and ground up homes that are reshaping some of the area’s most established streets.

This moment has been fueled by a clear and consistent demand: Affluent buyers have continued to be drawn to brownstone Brooklyn, especially to Brooklyn Heights, Cobble Hill and Park Slope. The luxury segment has remained surprisingly resilient, with a love for historic architecture paired with thoughtful modern craftsmanship.

Prices reflect that enthusiasm. Last quarter, the average price per square foot in Brownstone Brooklyn reached a record high of $2231, a figure that seems to climb every few months.

For developers, none of this happened overnight. Only a few years ago, even beautifully restored townhouses could sit on the market. Today, projected sellouts in the $15-$20 million range are not just feasible but common enough to attract both seasoned developers and newcomers who see an opportunity.

This is where the story becomes more complex: Single family development appears simple from the outside, yet the work requires precision and an intimate understanding of context. These homes must feel distinctive while still belonging to the surrounding block. They need to resolve the quirks of historic architecture with care. And in a place like Brooklyn Heights, a few hundred feet in either direction can determine whether a property achieves a record sale or remains on the market for months.

We are beginning to see both outcomes. A number of ambitious listings priced with peak optimism have struggled to find buyers. Others have achieved extraordinary numbers, but only in the most desirable locations and with exceptional execution.

Even so, the trend continues to build. Brooklyn Heights has become a testing ground for what luxury living looks like outside a luxury Manhattan tower. Its influence is extending into Fort Greene, Williamsburg, and Greenpoint, where record setting sales are beginning to chart a new map for Brooklyn’s highest end market.

As always, the story of New York real estate is a story of reinvention. One building at a time, one block at a time, and often through one bold idea.

Right now in Brooklyn, that story is being written through the townhouse, restored and reimagined, and shaping a new chapter in the borough’s understanding of luxury living.

The Shifting Landscape of Public Markets

I’ve been hearing more discussion lately about the shifting role of public markets. One perspective I found interesting came from Marc Rowan, Apollo Global CEO, who notes that public markets now represent a shrinking portion of the investable universe, a structural shift rather than a cyclical one.

I thought it's interesting to share this framework for thinking about how capital is moving and where value is increasingly created.

Since 2008, much of the regulatory reform in the U.S. has focused on banks. But as Marc Rowan points out, the broader markets have evolved in ways that regulators haven’t fully accounted for.

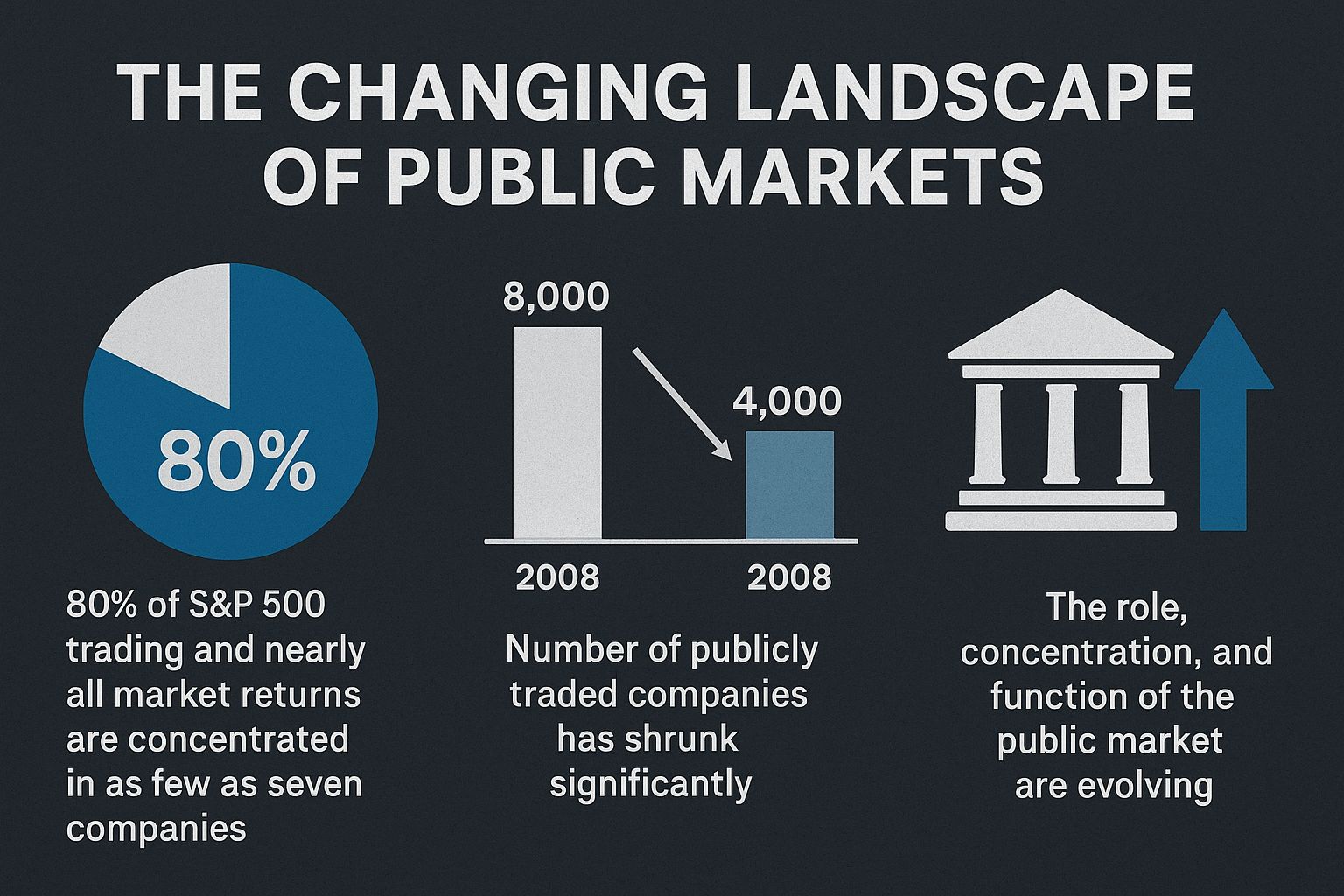

Today, the landscape of public markets looks dramatically different from 2008. Rowan highlights a striking reality: a huge portion of U.S. market returns now comes from just a handful of companies. In fact, roughly 80% of S&P 500 trading and nearly all market returns are concentrated in as few as 7 companies. He jokingly observes that the entire U.S. retirement system’s performance is “levered to Nvidia.”

Meanwhile, the number of publicly traded companies has shrunk significantly. What was once 8,000 companies has now become closer to 4,000, and the trend may continue downward. Rowan stresses that this isn’t due to regulatory burden but rather a shift in market structure. Many companies now have access to private markets that can provide debt and equity at scale, allowing them to stay private longer.

High-profile examples include Stripe, SpaceX, OpenAI, and even the NFL — companies that have chosen private markets over public listings. Rowan predicts we could see 50 to 100 very large companies electing to stay private because they can.

What does this mean for investors and the market? It’s a departure from the world many grew up in, where going public was the ultimate path to raising capital. The modern market offers flexibility, but it also changes how capital is allocated and where opportunities for public investors lie.

The public market isn’t disappearing, but its role, concentration, and function are evolving, and investors, regulators, and advisors need to understand that shift to navigate the new normal effectively.

If you’d like to receive my full newsletter, featuring insights on real estate, architecture, and curated city life straight in your inbox, sign up by clicking below: